Section Introduction:

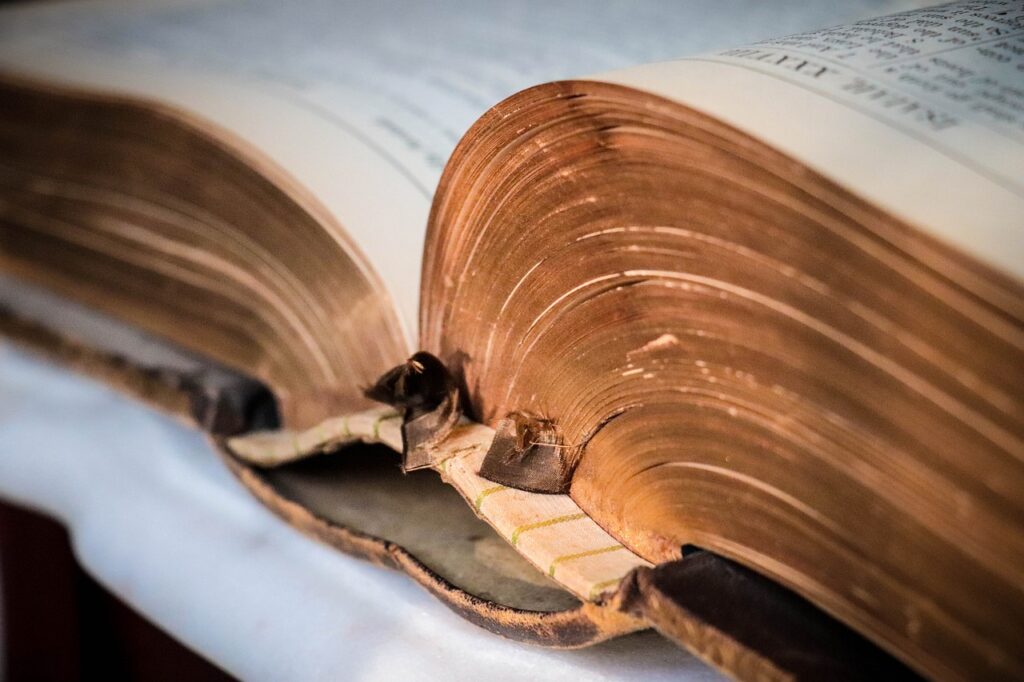

Few stories possess the enduring power and theological significance of the biblical creation narrative found in Genesis 1-2. From the account of creation ex nihilo to the crucial figures of Adam and Eve, the Genesis Creation Narrative stands as a timeless testament to the profound interplay between faith, reason, and the miracle of existence. The ancient text has sparked millennia of debate, contemplation, and interpretation, captivating the minds and hearts of many across countless cultures and civilizations. Since the late 19th century however, developments within science, textual scholarship, and cultural shifts have provoked an exponentially increased level of scrutiny and confusion surrounding how to interpret these two critical opening chapters. Through this series, I attempt to provide a comprehensive examination of Genesis 1-2 and the surrounding questions and controversies, exploring the depths of its symbolism, historical context, and theological implications. By navigating through the complexities of creation, the figures of Adam and Eve, and their various interpretations, we can shed light on the intricate complexity and beauty of this foundational text.

The Documentary Hypothesis:

Let’s be honest. Genesis 1-2 doesn’t appear as a cohesive literary work to us modern readers. Particularly troubling is the double creation of man. Why did the biblical author feel the need to mention the creation of man twice? This observation, along with many others of its kind scattered throughout the Pentateuch[1], caught the attention of scholars in the late 18th century. One of these scholars was a German biblical scholar and orientalist Julius Wellhausen. Today, Wellhausen is remembered for his groundbreaking and once widely accepted hypothesis known as the Documentary Hypothesis.

The Documentary Hypothesis is a scholarly theory that proposes the existence of multiple sources/documents as the literary sources for the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (known as the Books of Moses), suggesting that different authors or groups of authors wrote and edited these texts over time. According to this theory, Genesis 1-2 is composed of two distinct source documents. Genesis 1 is usually identified with the “Priestly” source, which presents a systematic and orderly account of the creation of the world, reflecting a characteristic style associated with this Priestly source. On the other hand, Genesis 2 is often associated with the “Yahwist” source, which presents a more focused narrative of the creation of humanity and the Garden of Eden. Moreover, supporters will point to the changing name of God within the Creation Narrative as an additional identifying characteristic found in each section. From Genesis 1:1 to 2:4, God is called “Elohim.” Then for no apparent reason, a new name, “Yahweh,” is introduced.

At first glance, the evidence appears very compelling. It is not surprising that modern critical scholarship has heavily favored the theory. However, a closer examination of the historical context of the text reveals evidence that significantly challenges the assertions of the Documentary Hypothesis. In this section, I aim to analyze the structure of the creation narrative (Genesis 1-2) within its appropriate context and test the Documentary Hypothesis claims surrounding it. In doing so, I propose that we unveil remarkable insights into the author’s literary mastery and begin to appreciate the truly breathtaking nature of the two introductory chapters.

The Question:

The crucial question we must address is: would this interpretation of two separate sources in Genesis 1-2 be the same for the Ancient Near Eastern readers—the original audience of the work? While the double-creation account may seem foreign to us, evidence suggests that it might have been far more familiar to the people of the ancient Near East.

Near Eastern Origin Stories:

When exploring other Near Eastern origin myths and primeval histories, the primeval history of Sumeria cannot be overlooked. Commonly known as the “Enki and Ninmah” story, scholars trace its origins back to around 2000 B.C., a timeframe that overlaps with Abram’s departure from Mesopotamia to the Promised Land. The tale begins at the dawn of time when only the gods exist of whom find themselves burdened with labor. Frustrated by their toil, the gods complain to Nammu, Enki’s mother, who suggests that Enki creates “substitutes” to perform the work. Enki agrees, leading to the creation of humans. This marks the first stage of creation.

The narrative continues with a second phase that transpires when Enki and Ninmah become drunk. Ninmah challenges Enki to a contest of crafting creatures, each with unique weaknesses. Despite Ninmah’s attempts to create beings with survival challenges, Enki finds a purpose for each weakness, ensuring their survival. In return, Enki challenges Ninmah to declare the fate of a being he creates—Umul, a weak creature born from a woman Enki impregnates himself. Nimah is perplexed by Umul’s condition, stating, ‘The man you have fashioned is neither dead nor alive; he cannot carry anything. It is often recognized by scholars that Umul is a newborn baby[2]. This then concludes the second creation account of mankind.

Another significant Near Eastern primeval history, perhaps even more predominant than the Sumerian myth, is the Atrahasis epic. The Akkadian version is one of the oldest stories from the Near East we possess dating back to the seventeenth century B.C. The epic begins by detailing a prehistoric and mythological era when the gods endured the burden of daily work. The laboring gods (the Igigi) subsequently launch a rebellion against the superior gods (the Anunnaki). In response to the revolt, the god Enlil requests the mother goddess, Mami, to create humanity and free the Igigi from their labor. With the assistance of the magician god Enki, she brings humans into existence. As you may reasonably deduce, the narrative closely mirrors the Sumerian Story of Enki and Ninmah.

Notably, the Atrahasis Epic includes another account of the creation of man that follows directly after the one explained above. This second, more specific creation of human pairs, designed for labor and reproduction, is presented directly following the aforementioned narrative.

Conclusion:

In summary, we see this dual creation of man in two major Ancient Near Eastern primeval histories dating from 2000-1700 B.C. Much like Genesis 1-2, both narratives commence with a broad overview of the creation of man, followed by a more detailed and specific account of human creation. This certainly suggests that this structural approach was a prevailing literary technique in the Near East. As Near Eastern scholar Isaac Kikawada states in his book “Before Abraham Was”, the biblical author of Genesis 1-2 appears to have put new wine in old bottles by employing the age-old mythic structure found in Ancient Near Eastern creation accounts[3].

The historical context sufficiently addresses the dual creation of man that Wellhausen and supporters of the Documentary Hypothesis refer to as evidence. However, while the dual creation structure initially appears to be merely a literary structure, its significance extends beyond mere narrative technique. As we dive deeper into the examination of Genesis 1 in the following post, it becomes apparent that this structural feature hints at a broader intention of the author within the text.

Sources:

[1] The Pentateuch (which Jews call the Torah) includes the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

[2] Kilmer, “Mesopotamian Concept,” pp.165

[3] Kikawada, Isaac M., and Arthur Quinn. Before Abraham Was. Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2017. pp. 39