Introduction

Following the account of the Fall of Mankind, Genesis 1-11 only increases in its already great complexity. The final eight chapters of the primeval history of Genesis include three major stories: the narratives of Cain and Abel, the Great Flood, and the Tower of Babel. Each of these narratives are unique and crafted with literary beauty and mastery, communicating major theological truths and historical insights. At the same time, one also finds the stories are intentionally connected and share underlying themes. This series of posts will delve into each narrative, exploring their intricate interpretations and the theological messages they offer.

Sacrifices of Cain and Abel

Now Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived and bore Cain, saying, “I have gotten a man with the help of the Lord.” And again, she bore his brother Abel. Now Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the ground. In the course of time Cain brought to the Lord an offering of the fruit of the ground, and Abel brought of the firstlings of his flock and of their fat portions. And the Lord had regard for Abel and his offering, but for Cain and his offering he had no regard. (Genesis 4:1-5)

When Adam is sent away from the Garden to cultivate the land by the sweat of his brow, his first-born son, Cain, joins him in the family labor. In ancient Near Eastern cultures, and practically all ancient cultures throughout the world, the first-born son inherited land from his father. Therefore, just as Adam works the land, Cain follows in his footsteps. While there is a logical and practical explanation for this practice, it often left the other sons with much smaller and subordinate portions of inheritance. They bore the responsibility of having to carve out their own path. Adam’s second son, Abel, in an inferior status and situation than his older brother, would have to make his way as a shepherd.

After some time, Cain and Abel each bring sacrifices to God. The text, importantly and intentionally, provides and/or excludes details regarding each of their offerings. Abel’s offering is described as being from the firstborn of his flock and their fat portions. The description indicates Abel offered his best to God. His sacrifice was made in a pure-hearted and benevolent manner. On the other hand, the text leaves out any further description of Cain’s offering of the fruits of the soil. Why? Well, this silence is clear: Cain’s offering lacked the wholehearted devotion and sincerity that characterized Abel’s. Because of this, God accepts Abel’s sacrifice and disregards Cain’s. The acceptance of Abel’s sacrifice and the rejection of Cain’s underscores that God values the heart and intention behind an offering. St. Augustine understood the story in this exact way—that Cain gave God a part of his goods, but he did not give Him his heart1. The narrative illustrates that true devotion requires giving God our entire selves in a complete and total sacrifice, a concept Christ himself would preach in his ministry on Earth nearly a thousand years after the publication of this story.

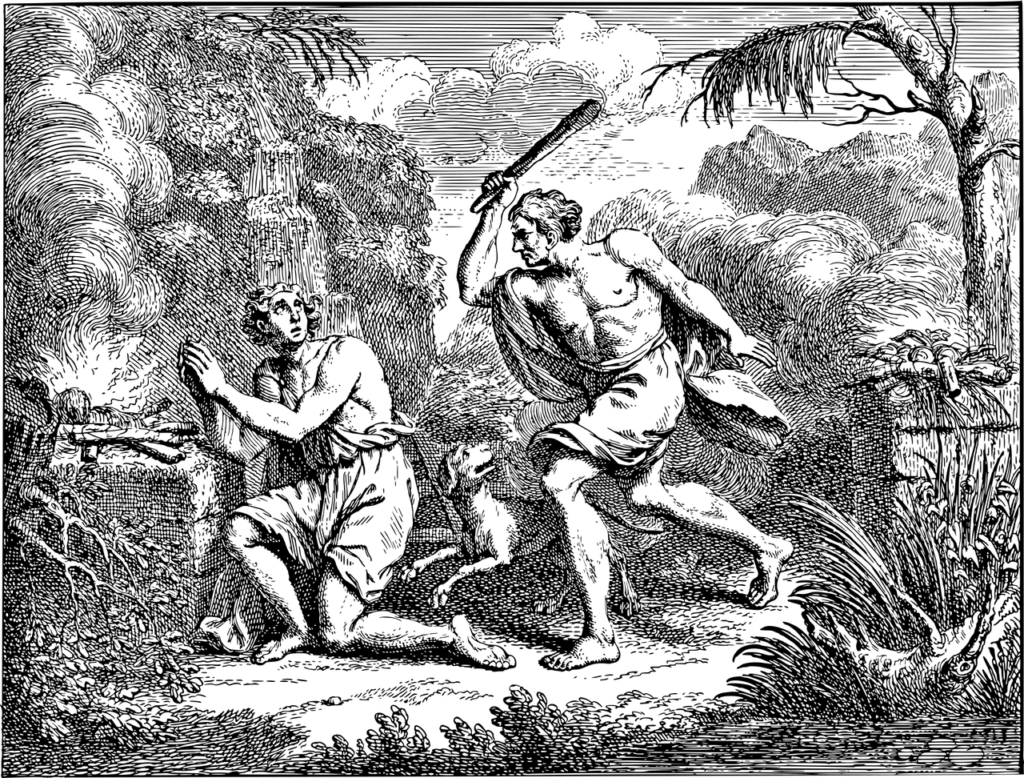

Cain’s Anger and The Murder of Abel

So Cain was very angry, and his countenance fell. The Lord said to Cain, “Why are you angry, and why has your countenance fallen? If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is couching at the door; its desire is for you, but you must master it.”

Cain said to Abel his brother, “Let us go out to the field.” And when they were in the field, Cain rose up against his brother Abel, and killed him. Then the Lord said to Cain, “Where is Abel your brother?” He said, “I do not know; am I my brother’s keeper?” And the Lord said, “What have you done? The voice of your brother’s blood is crying to me from the ground. And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you till the ground, it shall no longer yield to you its strength; you shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth.” Cain said to the Lord, “My punishment is greater than I can bear. Behold, thou hast driven me this day away from the ground; and from thy face I shall be hidden; and I shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth, and whoever finds me will slay me.” Then the Lord said to him, “Not so! If any one slays Cain, vengeance shall be taken on him sevenfold.” And the Lord put a mark on Cain, lest any who came upon him should kill him. Then Cain went away from the presence of the Lord, and dwelt in the land of Nod, east of Eden. (Genesis 4:6-16)

The story continues with a discourse between God and Cain. Although preferring Abel’s sacrifice, God engages in a dialogue with Cain, rebuking him and reminding him of the importance of free will. Cain, even under the burden of Original Sin brought upon him by his parents, retains the freedom to choose in the face of evil. This is a crucial theological message, as it applies not only to Cain but to all of humanity. Scholar Jordan Peterson in his commentary on the narrative notes that man is not predestined to evil; even in our fallen condition, we all have the choice to turn against evil, just as Cain does here.

Peterson continues his evaluation by discussing the choice God presents to Cain: to do well and be accepted, or to do not well and succumb to sin and evil. Sin is commonly interpreted here as a wild beast crouching at the door of the heart, ready to pounce upon its victim. Even after his sacrifice fails, Cain has the opportunity to shut the door on sin, take control of his life, make the proper sacrifices, and restore order. However, he does not. Dissatisfied with God’s response, Cain’s anger turns into rage not only against the universe but also against God. Much like his father, Adam, Cain opens the door to sin, allowing it to consume him and his entire consciousness2.

The tragic tale of jealousy and anger culminates in Cain killing his younger brother Abel. This chilling act is carried out in a diabolical and pathetic manner, separated from their family and executed without warning. It serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of uncontrolled anger and jealousy. It is a warning against the consequences of these sins. As he did with Adam and Eve, God again shows mercy and mitigates the punishment warranted by the actions of the sinner. While just five chapters later Genesis 9:6 explains how Cain’s murder of another human being warrants his own death, God spares Cain and sends him away from the original family and into the Land of Nod. While the narrative of the murder is more or less clear-cut, it is gut-wrenching and vastly important. Cain, and his identity as the first murderer, will be a pivotal association in the proceeding chapters.

Genealogy of Cain

Cain knew his wife, and she conceived and bore Enoch; and he built a city, and called the name of the city after the name of his son, Enoch. To Enoch was born Irad; and Irad was the father of Mehu′ja-el, and Mehu′ja-el the father of Methu′sha-el, and Methu′sha-el the father of Lamech. And Lamech took two wives; the name of the one was Adah, and the name of the other Zillah. Adah bore Jabal; he was the father of those who dwell in tents and have cattle. His brother’s name was Jubal; he was the father of all those who play the lyre and pipe. Zillah bore Tubal-cain; he was the forger of all instruments of bronze and iron. The sister of Tubal-cain was Na′amah.

Lamech said to his wives:

“Adah and Zillah, hear my voice;

you wives of Lamech, hearken to what I say:

I have slain a man for wounding me,

a young man for striking me.

If Cain is avenged sevenfold,

truly Lamech seventy-sevenfold.”

And Adam knew his wife again, and she bore a son and called his name Seth, for she said, “God has appointed for me another child instead of Abel, for Cain slew him.” To Seth also a son was born, and he called his name Enosh. At that time men began to call upon the name of the Lord. (Genesis 4:17-26)

One would be hard-pressed to find things less interesting to the modern reader than the genealogies of Genesis 1-11. They are scattered throughout the chapters in an often “boring” and systematic structure. Yet, these genealogies, especially the genealogy of Cain, are crucial to understanding not only Cain’s identity but the overarching themes of the eleven chapters. In previous discussions, including “The Examination of Genesis 1” (Post #6), we concluded that the biblical author intentionally draws comparisons and contrasts with the ancient creation accounts in order to underscore the distinctiveness of the biblical worldview and rebuke the pagan culture of the Near East. Here, in the genealogy of Cain, the biblical author takes another devastating blow at Israel’s surrounding neighbors.

Cain’s Wife

The genealogy begins with Cain and his wife conceiving a son, Enoch. Some may raise an eyebrow at the fact that Cain now has a wife. The narrative up to this point has only mentioned four humans: Adam, Eve, Abel, and Cain. Where did this wife come from? For those who interpret the text literally, this could be confusing. However, as we discussed in Post #7, it’s plausible that there were other anatomically modern humans living alongside Adam’s descendants. This suggests that Cain’s wife could have come from these other “humans”, who, while anatomically identical, did not possess the same rational human soul. If our theory holds true, the marriage between theological humans and non-theological humans (that is, humans without the modern soul) wouldn’t necessarily be an uncommon phenomenon in the early stages of human history.

Enoch

Nonetheless, the more critical figure here is Enoch. To uncover the veiled importance of Enoch, we must look deeper into ancient Near Eastern genealogies. As Near Eastern scholar and Yale Divinity School Professor Robert Wilson explains in his book, Genealogy and History in the Biblical World, ancient Near Eastern genealogies commonly attribute the city builder second on the genealogical list (behind the founder), and this builder would name the city after his son. Thus, we, and the ancient Near Eastern audience familiar with this common structure, would expect that Enoch would be the builder and the city named after his son, Irad3.

Remarkably, the ancient Sumerians considered the first city in the world as Eridu. While Irad and Eridu at face seem to be referencing different cities, scholar Isaac Kikawada observes the similarity of the names while simultaneously acknowledging the difference in language as the reason for the slight differences4. Moreover, he is not unique in his observations. Even among critics such as William W. Hallo and Wilson himself, there is a widespread scholarly belief that Irad and Eridu are, in fact, referencing the same city. With this established, an astonishing message employed by the biblical author unfolds: the genealogy is manipulated to specifically attribute the first murderer, Cain, as the founder of Sumerian civilization. As Kikawada explains, “As striking as it is for us to have Cain found the first city, it would have been even more striking to an ancient Near Eastern audience familiar with traditional genealogies”5. For us readers today, this message is hidden unless careful study is conducted. For the original readers and listeners, this message would have been unmistakable: Sumerian civilization is the work of a jealous, anger-filled, and murderous brother.

The intricate messaging of the genealogy does not end here. The line continues till we reach Lamech, a crucial figure who will be touched on later in this section. We are then greeted with Jabal, described as the father of tent dwellers and those who have cattle, Jubal, described as the father of those who play the lyre and harp, and Tubal-cain, described as a metalworker of bronze and iron. Here, it is important to revisit the conclusion drawn from this genealogical study thus far. Cain is the founder of the first Sumerian city and, by extension, Sumerian and associated Near Eastern civilizations. Consequently, it seems the rest of the genealogy is illustrating the developments and innovations connected with these civilizations.

With this in mind, the inclusion of Jubal and Tubal-cain is evident: Regarding Jubal, the Sumerians invented the lyre and harp around 3500 B.C., which were used to play royal songs of praise, accompany conquering armies, and provide private amusement. They were also very significant liturgically, leveraged by priests and priestesses to communicate with their gods. Regarding Tubal-cain, the Sumerians were also revolutionary in their metalworking. They introduced a method of creating harder forged metal by combining copper with other metals, practically inventing metalwork as we know it today. Important to note is the fact that the fruits of Jubal and Tubal-cain are not intrinsically evil in nature. While they could be twisted to be used in evil ways (such as pagan worship and crafting weapons for unjust warfare), and certainly were, it seems the biblical author here is merely highlighting major developments of Sumerian society.

Jabal

However, amid Jubal and Tubal-cain are Lamech and Jabal. It is with these two descendants that the biblical author highlights major sinful developments birthed from the Sumerians. For Jabal, it can be tricky to see how he represents an evil innovation. He is simply mentioned as the father of those who dwell in tents and have cattle, neither of which are sinful enterprises. Additionally, tent dwelling and livestock raising were not exclusive to the Sumerians or any other Near Eastern civilization; both practices can trace their roots thousands of years before these societies emerged. So, why is Jabal descended from Cain? The difficulty in articulating this seems to stem from the English translation. The word translated as “cattle” in this verse is originally the Hebrew word miqnēh6.

Miqnēh means ‘animate possessions’ and is derived from the verb qānāh, which means ‘to buy’ or ‘to possess.’ Kikawada notes that a more fitting English translation might be livestock, as it emphasizes the legal and commercial aspects inherent in the original Hebrew word. Nonetheless, even this translation may miss the mark regarding what the biblical author is conveying here. When examining other uses of the word miqnēh, and its root qānāh in Genesis, things become much more clear. Genesis 13:2 reads as the following: “Now Abram was very rich in cattle (miqnēh), in silver, and in gold.” The verse describes the wealth accumulated by Abram for allowing the Pharaoh to take Sarai. It describes his inanimate wealth—gold and silver—and his animate wealth, which is encompassed by the word miqnēh.

Luckily, Genesis 12:16 lists these profits, which a chapter later summarized as his miqnēh: “And for her sake he dealt well with Abram; and he had sheep, oxen, he-asses, menservants, maidservants, she-asses, and camels.” What we find is striking—the word miqnēh includes slaves under its broad umbrella of meaning. This is further evidenced in Genesis 47:19 when Joseph hears the desperate plea of his brothers: “Buy (miqnēh) us and our land for food, and we with our land will be slaves to Pharaoh.”

Could the biblical author thus be attributing Jubal as the father of slavery? Given the overarching tone of the genealogy, as well as the historical evidence that accredits Sumer as the birthplace of slavery, it seems more than likely. Hidden under the broad and unfortunate translation of “cattle,” the biblical author is, in reality, furthering his indictment by crediting the pagan Sumerians as the fathers of the flesh trade, who dwell in their luxurious tents bought with the extraordinary wealth gained from such a grave evil.

Lamech

Now to discuss Lamech, whose song and description take center stage in the genealogy. Crucially, the very first description of Lamech offered by the biblical author is that he has two wives. He is the first person in the entire Bible explicitly described as practicing polygamy. Why does the biblical author provide such a subtle detail? A quick look at Lamech makes this quite evident: the text blatantly associates polygamy with his violent and vengeful nature. It is an explicit moral critique of the practice. While we will see admirable people practicing polygamy later in Genesis and throughout the Bible, the action often comes with consequences that highlight the underlying issues and conflicts it brings. The biblical author makes it quite clear from the start—polygamy is wicked and contrary to God’s command that marriage is a monogamous, lifelong covenant as indicated in Genesis 2:24.

While the connection between polygamy and the figure of Lamech is widely noted, he is most commonly known for the song he sang to his wives, Adah and Zillah. The song is succinct and brutal, with Lamech boasting about killing a man for wounding him and a young man for injuring him. Lamech is seemingly the most brutal descendant of Cain in the entire genealogy. Given the theme we have established throughout this section, detecting the message the biblical author is attempting to convey is quite simple. Lamech and his song reflect the increasing violence and sin of Sumer and the surrounding nations. He demonstrates the degeneracy of Sumerian culture, priding himself on valuing human life even less than their founder, Cain.

Conclusion

Having examined the genealogy in Genesis 4, it becomes apparent how critical it is to the broader narrative of Cain and Abel. One might reasonably argue that the account of Cain and Abel serves as a prelude to the genealogy, which carries significant thematic weight across both chapters. While this perspective may appear radical, it certainly is the case that the story and the genealogy are intrinsically linked and must be considered together to fully comprehend the narrative’s depth and meaning.

The final question I wish to raise is this: Who were Cain and Abel? Were they historical figures, or are they merely symbolic or allegorical? Whether or not Cain and Abel were historical figures, the author’s intention was clearly to convey specific messages through their story and genealogy. These themes are the central focus of the narrative. In the story of Cain’s murder of Abel, the author emphasizes the necessity of giving oneself fully to God with a sincere heart, the consequences of sin and jealousy, and the power to resist wrongdoing even in a state of Original Sin. The genealogy critiques ancient Near Eastern civilizations, attributing their origins to Cain—the first murderer in history. Figures like Lamech and Jabal further illustrate the wickedness emanating from Sumer and Israel’s pagan neighbors. The narrative’s profound theological messages, rather than the historicity and identity of Cain and Abel, are what matter most.

In conclusion, Genesis 4, particularly the genealogy, establishes a foundational theme that permeates the remainder of the Primeval History. The biblical author’s use of heavy symbolism, manipulated genealogies, and the condemnation of pagan nations are paramount until we reach the story of Abram. As we progress through the next six chapters, we must adopt the perspective of an ancient Israelite, comprehending the prevalent stories and literary techniques of the time. Employing this approach will continue to open our eyes to the intricate beauty and complexity embedded within the Sacred Scriptures.

Notes and Sources

[1] De Civitate Dei, XV, vii

[2] Kaczor, Christopher. “Jordan Peterson on Cain and Abel.” Public Discourse, 21 June 2018, https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2018/06/21861/.

[3] Robert Wilson, Genealogy and History in the Biblical World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977) pp. 13-58.

[4] Kikawada, Isaac M., and Arthur Quinn. Before Abraham Was. Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2017. pp. 55

[5] Kikawada pp. 55-56

[6] Kikawada pp. 56-57